The message printed out by the Future Machine has been written in response to an ongoing conversation between the artist and creator of the Future Machine, Rachel Jacobs and Dr John King, Senior Climate Scientist at the British Antartic Survey about how we think about, experience, understand and talk about climate change and future uncertainty. As a result, the Future Machine has been designed to respond to five different scientific datasets, which are represented by the dials on the machine and the message printed out by the machine. The Future Machine is also informed by research by the climate scientist Mike Hulme looking at the myths we all have about climate change and how this effects what we think will happen in the future, these are represented by the ‘myth’ dial on the machine and the type of quest you have received from the machine.

What Is Climate Change?

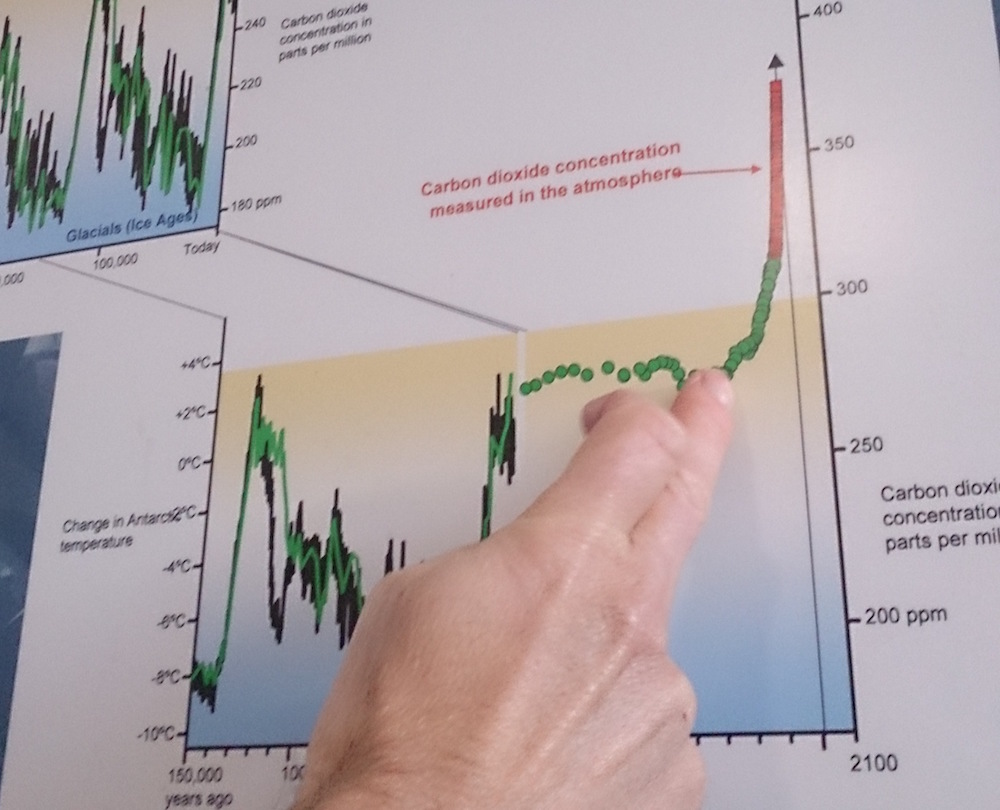

Climate is different from weather. Climate is the patterns and trends of weather in the Earth’s atmosphere, that are measured over a particular region, or throughout the planet’s atmosphere, over a long period of time (typically 30 years). Weather is what is happening in a particular place, over a shorter period of time. Climate Change is most commonly talked about in relation to human made (anthropogenic) changes in the earth’s climate (Norgaard 2011; Washington 2013; Wrigley 1999; O’Hare et al. 2005). The anthropologist Norgaard suggests that there are two basic facts that we need to be aware of in order to understand issues of anthropogenic (human made) climate change:

‘if global warming occurs it will be the result primarily of an increase in the concentration of carbon dioxide in the earth’s atmosphere… the single most important source of carbon dioxide is combustion of fossil fuels’ (Norgaard 2011)

There are differences between the terms ‘climate change’ and ‘global warming’. Climate change relates to all aspects of the Earth’s climate (which is very complex), whereas ‘global warming’ focuses on the Earth’s ‘increase of temperature over time’ (Boykoff 2011). Global warming has been seen as the ‘fingerprint’ or main sign that points to how humans have started to change the Earth’s climate (Wrigley et al. 1999). Ongoing social, economic and political discussions focus on whether and how we can put less CO2 (Carbon Dioxide) into the atmosphere (mitigation) and/or accept what is happening and find ways to deal with the consequences of our use of fossil fuels and our changing climate (adaptation).

Recently there have been calls by activists for governments and societies to call ‘climate change’ a ‘climate emergency’ and to respond to these changes with urgency, with the view that adaptation will not be enough to halt the spread of widespread extinctions, damage to land and sea, and threats to many of the lifeforms that currently exist on Earth (including humans).

Communicating Climate Data

Climate Scientists have been capturing different elements of weather and climate for a very long time. Since scientists started to be concerned about how much and how fast the Earth was warming in the 20th century they started recording data about the Earth’s climate, initially with a focus on global temperature and carbon dioxide levels. The temperature has been recorded in Central England since the 1675, this dataset is called the Central England Temperature Timeseries and this data is available freely on the UK MET Office website here: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadcet/

In climate science it has become conventional to use a 30-year baseline period. There is no fundamental reason for this choice but it was found, that climate data calculated over such a period were relatively stable. In a warming climate, statistics will diverge from those calculated for the baseline period the further you get from that period. It is therefore very important to make it clear what baseline period you have chosen. For example, the NSIDC interactive sea ice uses a baseline period of 1981-2010. The term “unprecedented” is favoured by scientists as it has an unambiguous way to describe something that you have not seen in your record so far (Arctic sea ice extent in September 2012 and UK maximum temperature on 25 July 2019 are examples). Of course an “unprecedented” value might be exceeded at some time in the future and, with a warming trend, such records are expected to be broken with increasing frequency. When classifying a value as “unprecedented” it is important to note that this is based on how far back the data goes. Please note that the Future Machine has been informed by scientific climate and weather data but interprets this data through dialogues with scientists and non-scientists, it does not aim to create a scientific climate model or representation. The Future Machine therefore aims to reflect on how we perceive climate change in our everyday lives and consider how things are changing over time – rather than considering only a scientific model of climate change.

How does climate change affect weather?

Although climate change is about the overall trends in weather, we are increasingly experiencing the effects of climate change on the weather we experience day to day, in our everday lives. As the overall temperatures of the Earth increase it changes the way weather works regionally and locally, for example in England the warmer Arctic influences currents in the North Atlantic ocean that controls the weather across the UK. Warmer seas effect how storms move and their strength. It can also have the opposite affect from what you would expect – as it creates weather ‘extremes’, creating polar, snow and hail storms in unexpected places (as was seen in Mexico in 2018). It is harder to prove that individual weather events are linked to climate change so we again have to look at the trends. What is being seen now is that the extreme weather events that we used to have in the past once in every 10 years are now sometimes happening once a year or more (as we have seen with the hurricanes in the gulf of Mexico and floods in India).

When the Future Comes… News From the Planet

When you receive your personalised ‘Future Quest’ from the future machine, you receive a story about the planet – the story that appears will depend on where you turned the dial (either on the actual Future Machine or using the Future Machine mobile app) that has the options for global, local, Arctic, Antarctic on it.

These news stories about the current state of planet Earth are based on the latest news and scientific climate data interpreted by Dr John King (Senior Scientist, British Antarctic Survey) in collaboration with artist/researcher Dr Rachel Jacobs who are in conversation about how to present environmental risk and uncertainty, and in a practical sense scientific climate data in ways that engage people in meaningful ways. One of the approaches they are exploring is how the data can inform a poetic description of the ‘news from the planet’. John sent this poem as Spring arrived after a cold winter (in 2021) influenced by a warming Arctic pushing freezing temperatures as far South as Texas.

Thaw Over the land freckled with snow half-thawed

The speculating rooks at their nests cawed

And saw from elm-tops, delicate as flowers of grass,

What we below could not see, Winter pass.

Edward Thomas